Data preprocessing in NLP

Data cleaning and data augmentation (not only) for text simplification

This is the second article about my project of text simplification using transformers. If you have not read the first one, feel free to do so, but it is not mandatory to understand this article. Feel free to check out the GitHub repo for this project.

Data preprocessing is not only often seen as the more tedious part of developing a deep learning model, but it is also — especially in NLP — underestimated. So now is the time to stand up for it and give data preprocessing the credit and importance it deserves. As in my first article, this one shall be inspired by the experience I had during working on text simplification. It will show some technics — their advantages and disadvantages as well as the idea behind them.

So let’s dive right in!

Data cleaning

Text as a representation of language is a formal system that follows, e.g., syntactic and semantic rules. Still, due to its complexity and its role as a formal and informal communication medium, it does not reach nearly the formality it needs for easy (pre)processing. This is the obstacle we have to overcome in data cleaning in NLP. Likewise, this is the reason why we need data cleaning.

A look at a dataset quickly makes clear what it is all about. For the text simplification approach, I used multiple datasets. And then, sometimes you find simplifications like this:

Castleton is a honeypot village in the Derbyshire Peak District,

in England .

This short text about the tiny village of Castleton is simplified to this:

Derbyshire

This may shorten the text to a minimum, but I would not call this a simplification. So how can we conquer this? Calculating the cosine similarity may tell us how close the two versions are. Luckily there are multiple libraries that can help us. To calculate the cosine similarity, we first need to embed the texts. If you want to read more about word embeddings in general, there are plenty of texts about it — I highly recommend this one. In this article, I assume you understand vector embeddings.

For NLP, Gensim is an excellent and very useful project. We use their Doc2Vec library for creating document embeddings.

We load the Doc2Vec with a pre-trained model. Then we infer the vectors before we calculate the cosine similarity using the scikit-learn library. The result is a float telling us how close those two texts are:

0.04678984

That is what we expected. But unfortunately, Doc2Vec is known for not performing well if the texts are concise. And “Derbyshire” is not even a text but one word. We should try another library to see how it performs.

Spacy is a well-known library in NLP. It provides functionality for POS-tagging, lemmatization, stop-words, and also embeddings. The code shown above gives us a result of:

0.19534963

Now we find ourselves in some dilemma: Two different libraries, two different results. And 0.04678984 (Doc2Vec) and 0.19534963 (Spacy) are not close to each other at all. If we look at the various models they use, we may understand those differences a bit better. The model Doc2Vec is using was trained on the English version of Wikipedia. Spacy — on the other hand — is using GLoVes word vectors trained on the Commoncrawl corpus. The embedding size of 300 is identical for both models. For testing, we can use an identical sentence for the source and the target and see how both perform — we are expecting something very close to 1:

Doc2Vec:

0.9235608

Spacy:

1.0000002

After this short evaluation and trusting Spacy already for many other tasks, we continue using Spacy for now. So, not to forget, the job is to clean the dataset by removing all sentences with low cosine similarity. But what do we define as low? One empirical approach could be looking at records within the dataset with a low cosine similarity and finding an acceptable threshold.

‘Toes are the digits of the foot of a tetrapod .’

‘Toes are the digits of the foot of a animal .’

Gives us:

0.9701131

Obviously, we keep this record, right? For now, we do but let’s remember this for later. How about this:

‘It can cause a zoonotic infection in humans , which typically is a

result of bites or scratches from domestic pets .’

‘Pasteurella multocida was first found in 1878 in fowl c

holera-infected birds .’

We can see that both sentences are referring to the same thing — the Pasteurella multocida bacteria. But the second sentence is hardly a simplification of the first. Together they would complement each other, which is a clear indication that it is not a simplification. And with a cosine similarity of only 0.18766001 Spacy confirms our assumption.

But 0.18766001 seems low for a threshold. So we continue looking for something higher.

‘Zax Wang was a member of short-lived boyband POSTM3N .’

‘Wang was a member of POSTM3N .’

Cosine similarity:

0.61018133

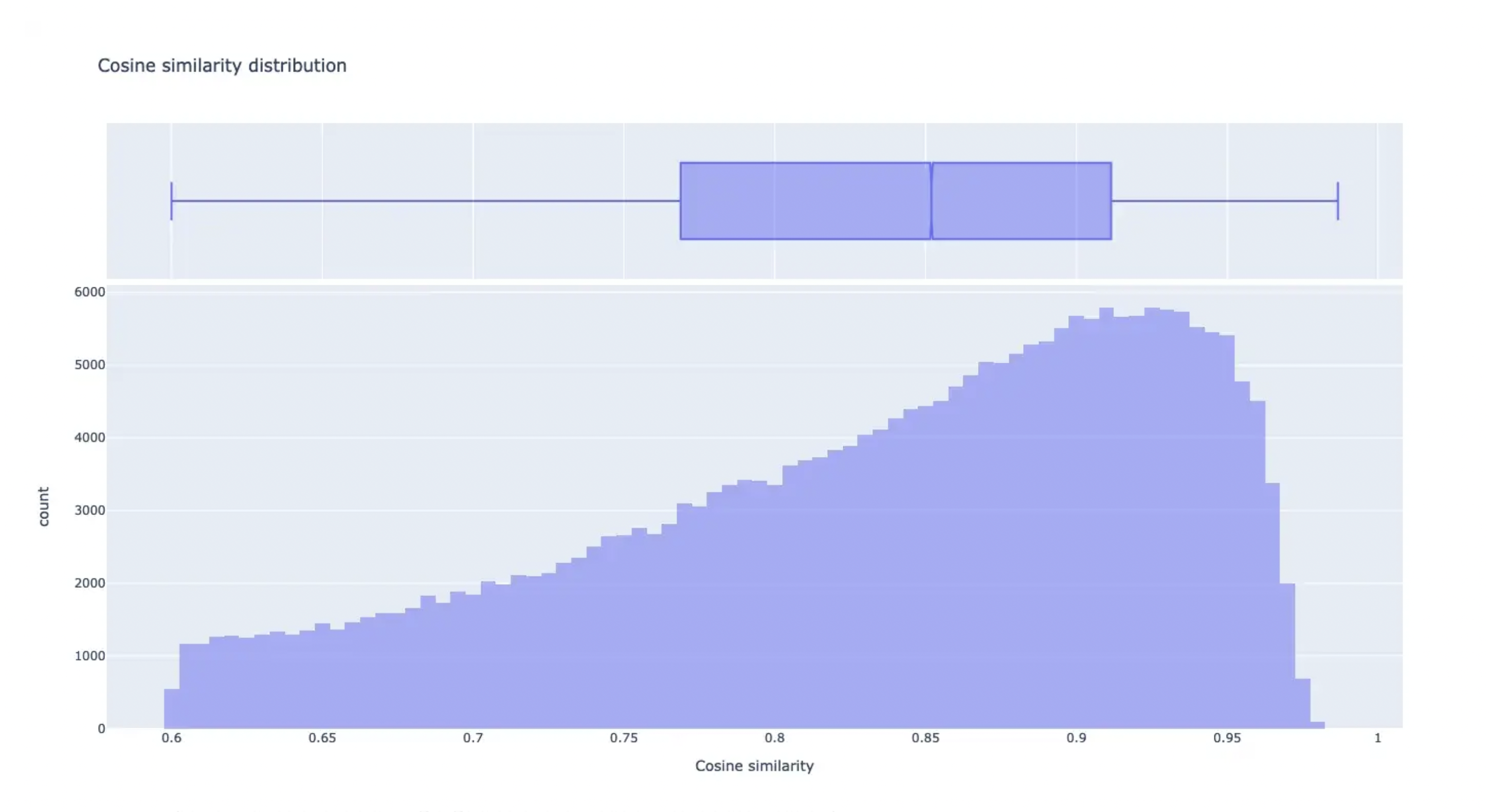

After a few more comparisons, we came up with a threshold of 0.6. But before we start cleaning our dataset and removing records with low cosine similarity, we have to talk about high similarities. What if we have a value of >= 99? That would imply that these sentences are very close to each other or even identical. And those records would not help our model to learn to simplify text but will decrease its performance. So we not only remove records with a cosine similarity below 0.6 but also with a similarity above 0.985. The outcome has this distribution:

With this method, we removed more than 40,000 records from the dataset. This not only shrunk it but also raised its quality.

What’s next? Any other ideas on how to improve the dataset? Spacy can do so much more than just creating embeddings. How about removing stop words or using lemmatization?

Stop words are known as being the most common words in a language. There is no universal list. But libraries like NLTK or Spacy provide them out of the box. The idea sounds appealing. But what do we expect from it? There are many approaches where the removal of stop words can improve the performance of the training ergo also of the model. In text classification, words like ‘the’, ‘this’ or ‘and’ don’t transport any valuable meaning and therefore no helpful information. But if they are seen as part of the sentence syntax, they are crucial for creating output. In other words: if the model is a sequence-to-sequence model and we expect it to create human-like sentences, then we can not ignore stop words and other non-informatical parts of the language. The same applies to lemmatization. This linguistic process of grouping the inflected forms of an expression may only remove a small amount of the carried information but disturb the model of handling natural language. Also, most pre-trained tokenizers are not trained on lemmatized text — another factor for decreasing the quality.

Another appealing simple idea is to remove too short sentences. With this, we would remove broken simplifications like this on:

Magnus Carlsen born Sven Magnus Carlsen on 30 November 1990 is a Norwegian

chess Grandmaster and chess prodigy currently ranked number one in the

world on the official FIDE rating list .

is simplified to:

Other websites

No idea how such a strange text simplification came about. But it is a perfect example why data cleaning is necessary, isn’t it? Removing sentences shorter than — let’s say — three words would throw away many broken records. But luckily, we are already handling this. Our cosine similarity algorithm would have removed this sentence with a similarity of only 0.15911613 anyway. An advantage of using this solution and not removing sentences by length is that we keep valid but very short texts.

It seems that the cosine similarity method — using an appropriate threshold — is a simple but powerful way of cleaning a dataset for text simplification in only one step.

Data augmentation— creating text from nothing

When data cleaning is the holy grail for a better performing model, data augmentation is the discipline of kings. I admit this one is a bit exaggerated, but especially in NLP, the creation of new data proves to be a tough challenge. This is where computer vision and natural text processing part ways once again. While computer vision models are often satisfied with getting turned, mirrored, or upside down copies of already existing images, NLP models — due to the language structure — are unfortunately much more demanding. But let us continue to be inspired by computer vision. Out approach shall be to create new text out of already existing ones.

The story about Abraham is a part of the Jewish,

Christian and Islamic religions .

to:

The religions of Christian is a part about the Jewish,

Abraham and Islamic story .

Even with an algorithm respecting verbs, nouns, adjectives, etc. (for example, using Spacy’s POS-tagging), the outcome can easily be excessive garbage. So as long as this is not done by mechanical Turks, this method seems unrealistic to provide good results.

But besides this syntactical modification, we may try a more vocabulary-driven approach: synonyms. Due to Python’s excessive collection of libraries, there is also one for equivalents.

First, we will have a look at the PyDictionary library:

This prints:

['snake', 'moon', 'dry land', 'property', 'ice', 'catch', 'oddment',

'makeweight', 'ribbon', 'lot', 'stuff', 'peculiarity', 'web',

'physical entity', 'whole', 'hail', 'soil', 'terra firma', 'wall',

'floater', 'trifle', 'physical object', 'fomite', 'token', 'location',

'remains', 'part', 'formation', 'shiner', 'relic', 'paring', 'souvenir',

'portion', 'ground', 'charm', 'geological formation', 'earth', 'curiosity',

'small beer', 'neighbour', 'commemorative', 'vagabond', 'thread',

'good luck charm', 'film', 'vehicle', 'rarity', 'hoodoo', 'trivia',

'discard', 'curio', 'oddity', 'land', 'neighbor', 'unit', 'prop',

'filler', 'solid ground', 'growth', 'je ne sais quoi', 'head',

'triviality', 'draw', 'keepsake', 'finding']

Great start! We receive a list with different synonyms. Even if I have to admit that ‘snake’, ‘moon’, and ‘dry land’ are strange synonyms for ‘object.’ Maybe we should try another library. Next up — NLTK:

[‘object’, ‘physical_object’]

[‘hope’]

This looks more promising. NLTK found a smaller but more useful range of synonyms for ‘object’. It is worth playing with it a bit more:

Output:

‘angstrom three-dimensional object rotates always around Associate in

Nursing complex number line called angstrom rotation axis.‘

‘angstrom three-dimensional object rotates around angstrom line

called Associate in Nursing axis.’

Interesting with a lot of potential for optimization 🤔. Checking the cosine similarity to avoid having unsuitable synomys may look like this:

‘A three-dimensional physical object rotates always around AN imaginary

line called a rotary motion axis.’

‘A three-dimensional physical object rotates around a line called AN axis.’

This approach is going in the right direction. However, the code is not for a production system. The performance is simply not good enough yet. But we see that synonyms seem to open up the possibility of creating new texts based on existing ones. There are other libraries, such as py-thesaurus — but we will not go into them right now. Instead, we will jump directly to the next approach: Back-and-forth translation.

The idea behind this procedure is simple. We take a text, translate it to another language — let’s say German — and then translate it back to its source language. As usual, this should be automated so we could use the APIs of Google Translate or DeepL. I will not use the API in the following examples, but instead, I will use their website services. Let’s start playing with it by starting with Google Translate:

Source text:

A three-dimensional object rotates always around an

imaginary line called a rotation axis.

German version:

Ein dreidimensionales Objekt dreht sich immer um

eine imaginäre Linie, die als Rotationsachse bezeichnet wird.

Back to English:

A three-dimensional object always rotates around an

imaginary line called the axis of rotation.

Not too bad. It changed the text at least a bit. DeepL provides similar results. How does it work with longer or more complex texts? This time we try DeepL:

Source text:

Carol I of Romania , original name Prince Karl Eitel Friedrich Zephyrinus

Ludwig of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen , later simply of Hohenzollern

(April 20th , 1839) , German prince , was elected Domnitor

Prince of Romania on April 20th , 1866 , following the overthrow

of Alexandru Ioan Cuza .

German version:

Carol I. von Rumänien , ursprünglicher Name Fürst Karl Eitel Friedrich

Zephyrinus Ludwig von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen , später einfach von

Hohenzollern (20. April 1839), deutscher Fürst , wurde am 20. April 1866,

nach dem Sturz von Alexandru Ioan Cuza,

zum Domherrn Fürst von Rumänien gewählt.

Re-translated to English:

Carol I of Romania , original name Prince Karl Eitel Friedrich Zephyrinus

Ludwig von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen , later simply

von Hohenzollern (20 April 1839), German prince , was elected

Canon Prince of Romania on 20 April 1866,

after the fall of Alexandru Ioan Cuza .

Very nice — it is changing the vocabulary and the syntax a bit. This seems like a helpful method for augmenting new text. There is some more trying and research needed to get a feeling for its reliability and potential improvements, but this first very short insight looks promising.

Some ideas for future tries could, for example, be translating it into two different languages before translating it back to its origin. Maybe it also performs better if we use languages that are not both part of the Indo-European languages. There is so much more to discover, and I am optimistic that we can find a proper way of augmenting text for NLP. Suppose you have more ideas or experience with this. Please, share it with us!

That’s it for the second part about my experience working with NLP and text simplification. The next part will be about implementing and understanding the transformer architecture in detail. Until then — au revoir.